Your support helps us to tell the story

In my reporting on women’s reproductive rights, I’ve witnessed the critical role that independent journalism plays in protecting freedoms and informing the public.

Your support allows us to keep these vital issues in the spotlight. Without your help, we wouldn’t be able to fight for truth and justice.

Every contribution ensures that we can continue to report on the stories that impact lives

Kelly Rissman

US News Reporter

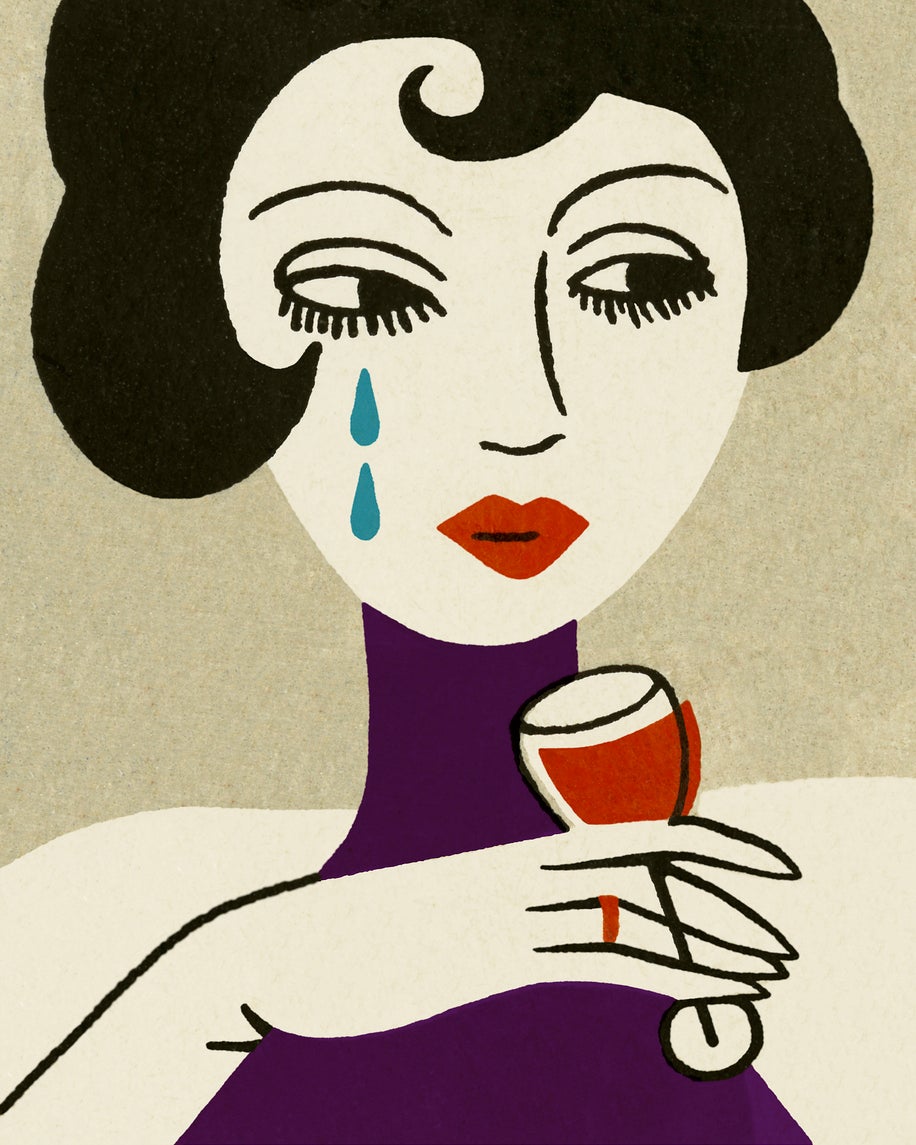

The scene goes something like this: girl sitting by an open kitchen window with her feet in the sink. The door is closed; her cat is curled up on the other side, meowing intermittently with concern. There is a cigarette dangling between her fingers in one hand. The other is curled around her third glass of wine of the evening. There is piano music playing, soundtracking the girl’s despair. She is alone. She is crying. She is drunk.

It sounds like something out of a botched Bridget Jones film. And yet, it was – for a time – something I performed regularly. I say performed because that’s what I was doing: playing the part of the sad, lonely (but chic!) girl, one who’d clearly spent far too much of her youth watching Sex and the City and attempting to cosplay Carrie Bradshaw. But I really did it a lot, particularly throughout the pandemic, when my drinking became an almost daily occurrence, and in the years that followed.

My point is that I was drinking at home often. And while it’s not something I do anymore, I was reminded this week of just how much I used to do it when I read that only 27 per cent of people aged 18 to 24 in the UK now own a corkscrew. Translation: today’s young people aren’t drinking wine at home (or wine with a cork, at the very least). To put it all into perspective a little, 81 per cent of over-65s own a corkscrew, according to Lakeland’s annual trends report.

It partly reflects the contemporary shift towards sobriety among Gen Z, who are far more likely to abstain from drink altogether – Nielsen data from last year showed that 45 per cent of those in that cohort who are over 21 said they had never drunk alcohol at all. Wine is facing a particular decline, with worldwide consumption dropping by 2.6 per cent last year, reaching the lowest levels since 1996, according to the International Organisation of Vine and Wine.

Meanwhile, in December, one millennial sommelier went viral on TikTok after asking her followers why they weren’t drinking wine. The clip, which racked up more than 1.6 million views, featured comments from people pointing to the high costs, the health risks, and other ways you can get your kicks, like mocktails. It’s a shame, in a way, and not just because the best wine tends to come with a cork as opposed to a screw-top. It also feels like a loss, as if we’ve all collectively decided to have a little less fun and indulge in fewer manic-slash-solipsistic episodes.

My at-home wine habit came about during the first lockdown, when I found myself seeking thrills wherever I could find them. At first, it was via a wine delivery service where you could mix and match various high-quality bottles (six for £45!). I’d have my wine in the evenings in front of the TV, and feel sorry for myself until I started to feel drunk. The idea of sinking a bottle of sancerre in front of a box set might sound like a millennial ideal, but the reality is that you often wind up feeling a bit blue — and later, rather discombobulated when you try to put yourself to bed. After a night of drinking at home, I’d wake up the following day, feeling even more self-pitying and vowing not to drink that night.

But by the time 6pm rolled around, I’d be drinking, framing it as an artistic choice because this was also around the time that I started writing my first book. I’d write by candlelight in the garden shed with a glass of pinot noir perched next to my laptop, thinking far more about the highly Instagrammable aesthetic of it all than the actual writing. I know, I know.

The wine delivery box evolved into nightly visits to my local wine shop. I’d enter with my housemates, and we’d peruse the shelves until we found a bottle we liked the look of and could envisage guzzling together in our kitchen. When summer arrived, and restrictions eased, this turned into rosé shared over picnics in our local park. We were all on a first-name basis with the owner of the wine shop.

Fast forward a few years and you’ve got the sad, smoking lady for whom drinking wine at home had become a clear indication that something was wrong. I did it if I’d had a difficult day at work. Or if I’d had an argument with a friend. Or if I was simply feeling rather low. My default was to buy a nice bottle of wine and enjoy it in the solitude of my own home (usually alongside a cigarette). The romance of it all was quite fun for a while. But it quickly became clear this was not a healthy habit, nor was it one that was making me feel any better.

If anything, it only made me feel worse, and signalled various absences in my life: of a partner, of friends to drink with that night, and of something deeper inside me I couldn’t seem to fill with malbec, no matter how hard I tried. So I stopped – and imposed a firm no drinking at home rule on myself. The only exception is for when I have friends over, which, by the way, is something that also seems to happen far less than it used to – death of the dinner party, anyone?

For me, drinking at home usually points to a sadness of some kind. It’s a defeat. Maybe that’s just me, and my association with it. But if I’m going to continue drinking alcohol (which I am, for now), I want to make sure it’s a joyful experience as opposed to a depressing one. And that means doing it out in the world, surrounded by friends – sharing silly anecdotes over crowded tables at the pub. Because the Bridget Jones picture I’d created was never quite as romantic as it might’ve looked; it was just a bit bleak.