Union Grove, North Carolina

Stephen Faust is a bit of a throwback, a description he doesn’t mind. The fifty-five-year-old North Carolina native breeds and trains Gordon setters in the spring and summer, and then guides hunts for woodcock and grouse. “Gordons just suit my style,” he says. “I want a classic foot-hunting dog.” While these handsome black-and-tan setters can open up in big country when they need to—a dog from Faust’s current litter is bound for the prairies of North Dakota—they’re better known as closer-ranging hunters. “I don’t want a dog I have to holler and scream for,” he says. “I want it to hunt for me, not the other way around.” According to Faust, the Gordon setter was once the dog of choice for market hunters but fell out of favor in the early twentieth century as field trials pushed breeds that ranged farther. “If you want a dog that’s out there at fifty to seventy-five yards,” he says, “pointing birds where you can actually get to them, then a Gordon could be the dog for you.”—T. Edward Nickens

Brainerd, Minnesota

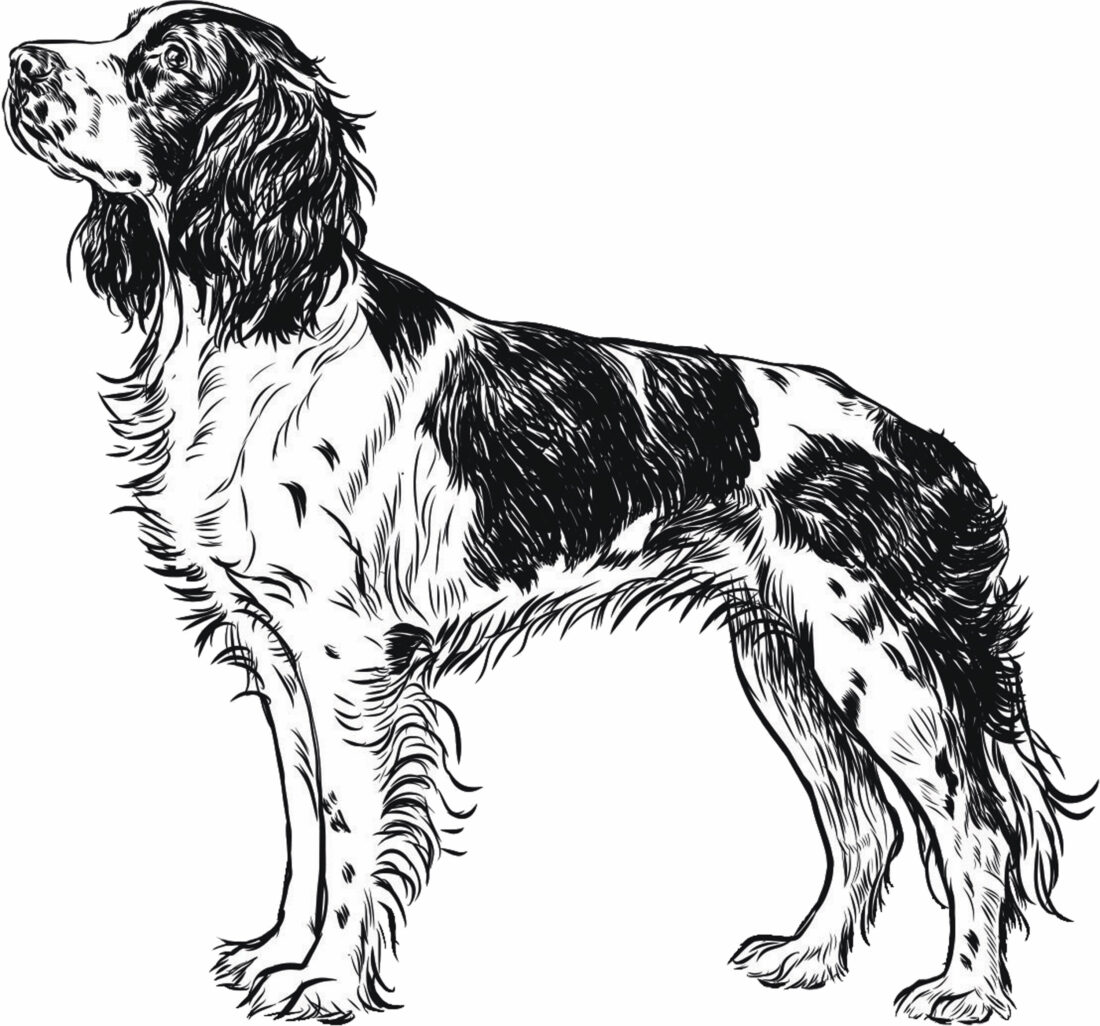

You might expect Mark Haglin, who’s been breeding English springer spaniels since 1976, to foremost tout the breed’s hunting acumen and intelligence. Instead, he says, “what I like most about them is their eyes, and that connection to the owner and the trainer.” Indeed, you’d be hard-pressed to find a more soulfully expressive gun-dog. Averaging about forty pounds and naturally inclined to stay within gun range while questing for birds, springers are especially suited to flushing upland pheasant and grouse. “A well-trained springer will smell a bird, pick up speed, and flush hard, then sit until it retrieves the fallen bird and presents it to you,” Haglin says. Pine Shadows keeps pups for a full ten weeks of socialization supervised by Mark’s wife, Sophie, fostering what the Haglins believe is an ideal blend of sporting and family dog. (Their son Morgan runs the training program for older springers and other breeds.) “They enjoy time off with the family,” Haglin says. “They look at you with a sense of ‘What can I do for you today?’”—Steve Russell

Scout, a seventeen-week-old English springer spaniel from Pine Shadows’ breeding program.

Brandywine Creek Boykin Spaniels

Greenfield, Indiana

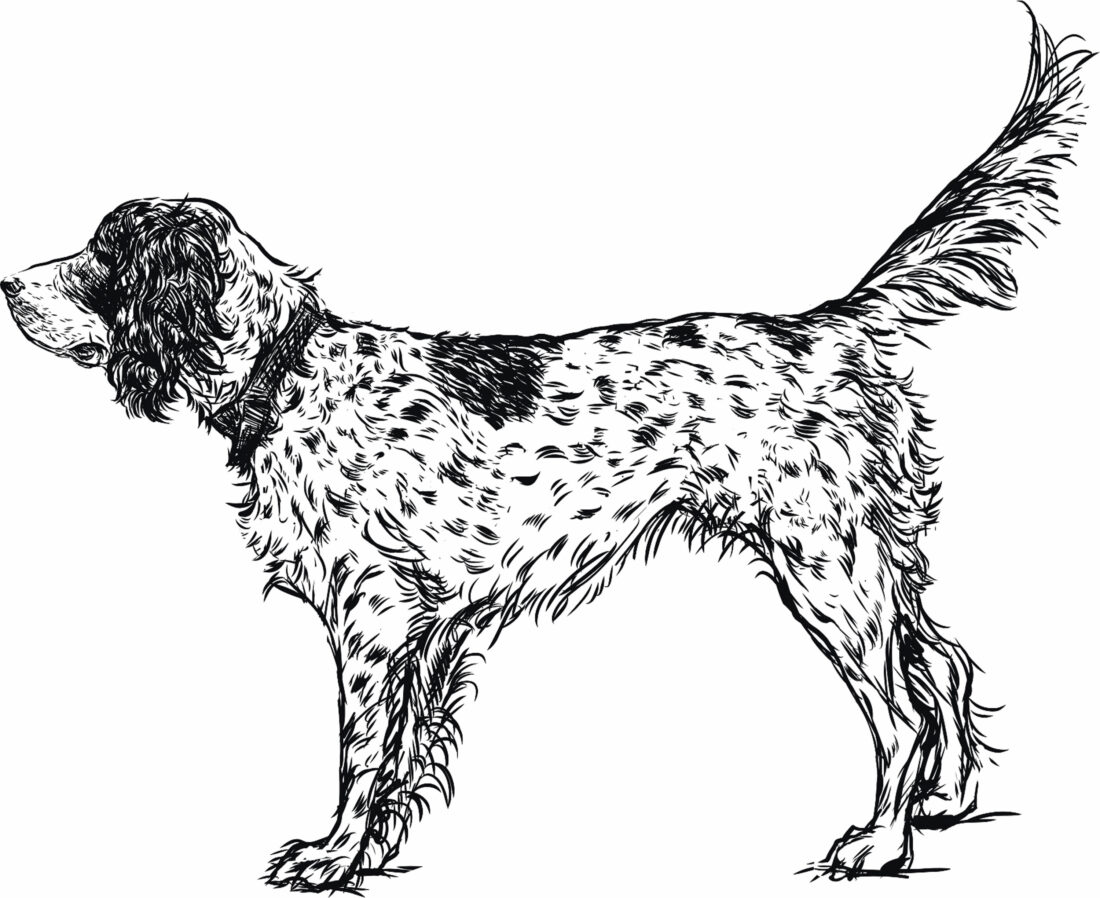

Of the three or four litters a year that Phil Hinchman makes available, he typically keeps a couple of pups, resulting in the baker’s dozen of Boykins currently at his heels. That suits him fine, because he fully appreciates the breed’s desire to stay close to an owner both around the home and in the field. Hinchman also thinks a Boykin possesses the best nose in the business and wields it to find birds other breeds have dashed past. “One time at a field competition,” he says, “another handler asked me, ‘Hey, what are you doing to make that dog’s nose so big?’” (He does have a nifty training trick: He tosses frozen birds into the yard at night for pups to retrieve in the dark by following very little scent.) “I see them as the all-around sport dog,” he says. “I’ve hunted pheasant, quail, grouse, and chukar, and it made no difference to the Boykins.” And he’s the first to tell you the water-loving breed excels in a duck blind, too. Are prospective owners also in danger of winding up with a pack? “They’re like potato chips,” he says, laughing. “You can’t have just one.”—SR

Pawhuska, Oklahoma

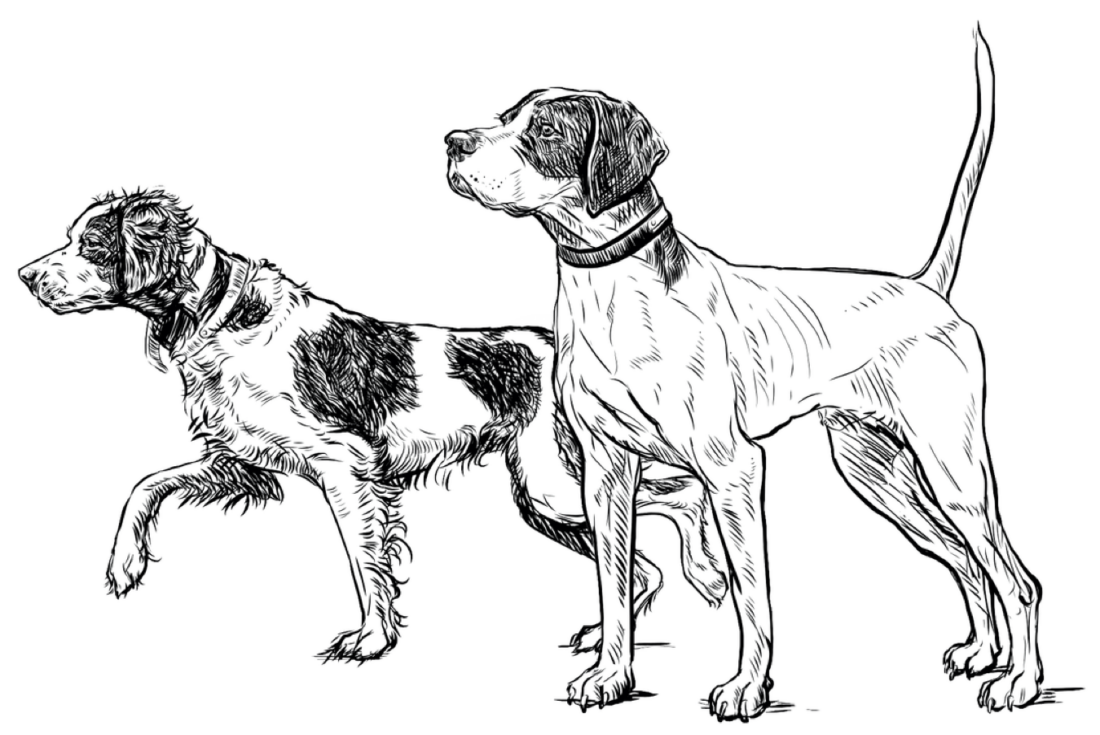

In addition to the buffalo and wild mustangs that call the rolling hills of Osage County home, Smith Kennels has made it known for gundogs, too. While bird-dog training is the backbone of the operation, established in 1956, second-generation owners Ronnie and Susanna Smith also produce a few litters a year, specializing in a bloodline of Brittanys that reaches back to Ronnie’s uncle, Brittany Field Trial Hall of Fame trainer Delmar Smith, and offering a small number of English pointers. While pointers may be the solid choice for quail in rugged, open country, Ronnie praises the versatility of a Brittany. “They make great pets in the home, and at the same time, you can put our dogs in the truck and go hunt smaller blocks of land. They’re highly trainable and focused in the field, and might do a better job in a pheasant field than a pointer.” Smith Kennels typically welcomes its pups back at a year old for intensive training, and it emphasizes matching pups with hunting families. “These dogs are athletes and motivated,” Ronnie says, “and need that kind of outlet.”—SR

Hope Hull, Alabama

Nothing against Micha, the black cocker spaniel that took top honors in the sporting category of the Westminster Kennel Club show this year, but poofy show dogs are a far cry from the bottled lightning known as the field-bred English cocker. At Covey Flush, Phil Gray breeds and trains these feisty hunters, which can flush, mark, retrieve, and all but grill a game bird and deliver it to you on a plate. More and more hunters are turning to field-bred cockers as flushing dogs on quail hunts, or as do-it-all companions in the dove field, duck swamp, and woodcock thickets. The term cocker, in fact, comes from the breed’s history. “The English had plenty of springer spaniels,” Gray explains, “but those dogs were a nightmare in the woodcock woods, as they tended to flush birds out of gun range in thick cover. They started taking the runtiest spaniels they had and turning them into woodcock dogs, which they called ‘cockers.’” Today’s field-bred cockers typically have more color variety than springers and run smaller, perfect for the canoe, skiff, or UTV.—TEN

Oxford, Mississippi

No one was more surprised than Wildrose owner Tom Smith when one of the kennel’s yellow British Lab pups, Juice, became a social media sensation upon his adoption by Ole Miss football coach Lane Kiffin in 2022. But even before that sort of exposure, Wildrose, founded in 1972, had long enjoyed a national reputation for breeding and training “gentleman’s gun-dog” British labs, which tend to be a bit smaller and more attentive than their American cousins. “We really like their temperament,” Smith says. “Laid-back, but with plenty of drive in the field, and they really know how to use that God-given thing on the end of their face that picks up scent so much better than we do.” While those noses have gotten Wildrose pups recruited as narcotics sleuths and diabetic-alert dogs, most are MVPs in quail uplands and duck blinds—or family living rooms. “They’re very versatile,” Smith says. “They can go duck hunting in the morning, eat some lunch, and head to the quail field in the afternoon, then be back at home chilling in the dog bed while I watch football.” Juice, of course, might prefer to watch a certain team more than others.—SR

Aiken, South Carolina

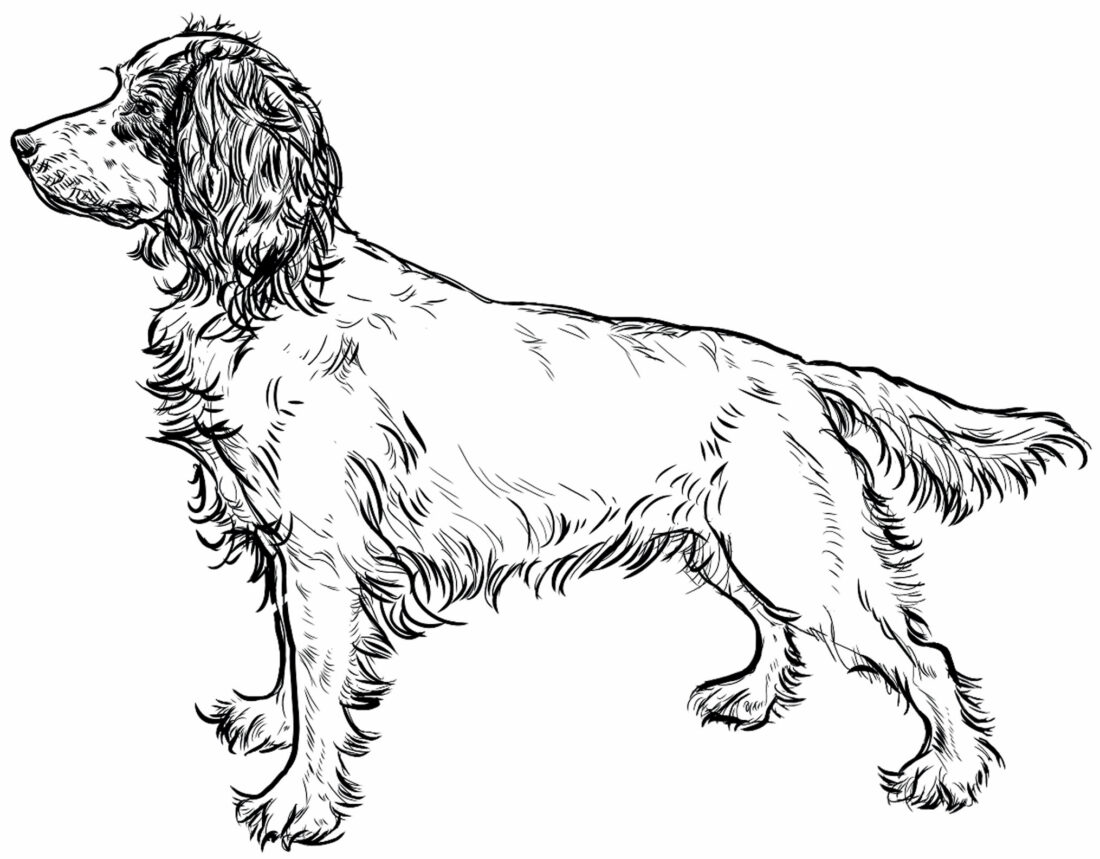

Part of Mark Fulmer’s philosophy of breeding and training pointing dogs is to get out of Mother Nature’s way. The owner of Sarahsetter will work a pregnant setter lightly until she’s ready to give birth. “Every wild animal in the world has to feed itself before giving birth,” he says. “That kind of stimulation is no different than playing music for an unborn child.” Then once the dogs are off their mother’s milk, they get a freshly killed quail as their first meal. “I’m duplicating what happens in nature: imprinting what those dogs will want to look for the rest of their lives.” A full-time trainer since 1991, Fulmer raises around three litters each year—two of English setters and a third of field-bred red setters, an Irish setter–English setter cross. He spends hours each day in the field with the dogs. By ten weeks of age, he says, an entire litter should be pointing, and most will be backing. By twelve weeks, the dogs are searching a fifteen-acre enclosure and pointing birds. But give him another month, he says, and they’ll have had forty birds shot in front of them. “When I send out four-month-old puppies, they’ve basically had their first field season.”—TEN