I have been fortunate in my life to work on a number of interesting projects, but I can say without reservation that being part of the team that made the documentary Jimmy Carter Rock & Roll President was one of the most rewarding.

I have long admired Jimmy Carter. I brought home a peanut souvenir from a school field trip to Washington, D.C., when he was president. As I got older I appreciated that he was such a decent human being. But my favorable perceptions increased in 2017 when I heard that Carter—a “fuddy duddy” character to so many people—was actually friends with the likes of Gregg Allman, Willie Nelson, and Bob Dylan. Not just friends but close friends.

I was so intrigued by this revelation I decided I wanted to make a film about it. Now, I had never made a documentary before, so it was a pretty big leap to think I could produce one about a former president and a bunch of rock and roll stars. But I enlisted my good friend, the award-winning documentary director Mary Wharton, and in turn we convinced legendary music journalist Bill Flanagan to join us.

Mary Wharton, President Carter, Chris Farrell, Amy Carter, and Chip Carter.

We then set about to get President Carter’s buy-in. We were told he received at least one documentary proposal a week and it was always rejected; in fact there had been no authorized documentary on Jimmy Carter since Jonathan Demme’s 2009 Man from Plains. But we benefited from collaborating with a number of former Carter staffers and members of the Carter Center, who were generous with their time, guidance, and support. (Over time we came to know this spirit of giving was present with almost everyone in the Carter orbit.) Eventually, with the blessing of those close to him, Carter agreed to let us move forward. We were told he appreciated the unexpected angle. I also believe that in some small measure his endorsement came from feeling comfortable with our backgrounds.

Mary and I are both from towns in North Florida that are geographically close to Plains and, in the early 1970s when we were growing up, very much resembled it. As Carter noted in an interview, “I knew based on their love of music, faith, determination, and Southern roots that Chris and Mary were right to tell the story.”

The story we tried to tell was one of hope, faith, compassion, redemption, moral courage, and the power of music to heal and bring people together. The soundtrack we used to tell it mirrored the president’s eclectic and—in the words of Carter’s longtime assistant, Frank Moore—“encyclopedic” knowledge of music. Sarah Vaughan and Lynyrd Skynyrd. Jimmy Buffett and Glenn Miller. Paul Simon and Dizzy Gillespie. Johnny Cash and U2. The Allman Brothers, Debbie Harry, Willie Nelson, Charlie Daniels, and Bob Dylan.

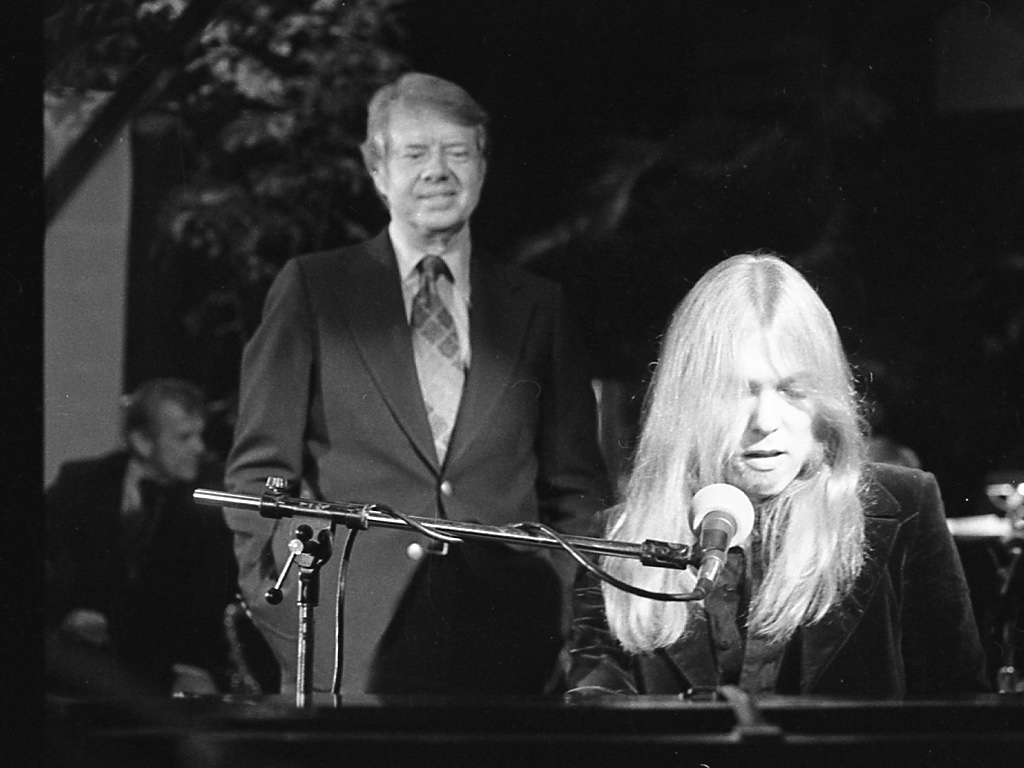

Gregg Allman performs at a campaign fundraiser in Atlanta in 1976.

Just as eclectic as the soundtrack was the roster of high-profile figures who participated in our film, clearly out of love and respect for Carter. The idea of servant leadership was paramount to Carter’s identity, and it resonated with everyone involved. To see how he lived this calling every day was instructive and inspirational, but two memories from filming stand out to me in particular.

The first took place in Plains. We had arranged to conduct our second sit-down interview with the president at the former home of his mother, Lillian. It was a hot and muggy day—so much so that the camera overheated and stopped functioning a few hours before the president was scheduled to arrive. Despite his seemingly easygoing style, President Carter, the former naval officer, demanded punctuality. The atmosphere was fairly tense, but Mary, ever the professional, remained calm.

Something I did not publicize at the time was that I had undergone life-saving open-heart surgery during the first few months of production. We had already started filming, but my illness had threatened to derail the project. After the operation I had to wear a PICC line, or catheter, to constantly deliver antibiotics to my heart. My doctors advised me not to travel, as an infection could put me in acute danger. It was probably not the smartest thing I have ever done, but I disregarded the warnings and headed to Plains for the second interview.

Due to the humidity, my PICC line clogged and I had to leave the shoot and rush to the hospital. I received immediate treatment—but now was an hour away from Ms. Lillian’s home, with the interview set to start in forty-five minutes. I won’t say how fast I drove, only that I might have disobeyed the speed limit. As I pulled into Ms. Lillian’s driveway, the replacement camera was also just arriving from Atlanta—five minutes before the president was due. When Carter arrived, it was a chaotic scene between the crew, secret service, and others. But he waded through everyone and found me. He put his arm on me and told me he and the First Lady had been praying for me and my recovery.

As long as I live, I will never forget that moment of kindness. It was just a small example of the compassion often seen at scale through his work with Habitat for Humanity or the Carter Center. My medical prospects were still shaky, but I am certain that Carter’s personal acknowledgement, my own faith, and the shared sense of purpose we felt as a team pulled me through to better health.

The second vivid memory relates to how Bob Dylan gave us the ending we needed for the film. It had been a challenge to coordinate logistics to get the interview. We all recognized that this was the “big one.” I remember Bill Flanagan, Jeff Rosen, and Dylan sitting and prepping. I remember Mary expertly handling the shoot, making Dylan and everyone else comfortable. And then the interview started and Dylan came alive as he spoke about Carter.

Dizzy Gillespie (center) brings Carter onstage at one of the White House concerts.

What finally appeared on screen is one of my favorite scenes in the film: Dylan’s words of affection and praise for Carter. The Lynyrd Skynyrd song playing in the background as Dylan recites the lyrics. And finally Carter’s own words—a call for each of us to try to be good human beings. To be intentional about how we live our lives. To say to ourselves, “This is the person I want to be.”

In the days following the president’s passing, I have been in contact with a number of people involved with the film, who expressed their sadness but equally their joy in having known him. Rosanne Cash shared the following words, which in her typical fashion are both eloquent and spot-on.

“You would think I love President Carter for how devoted he was to music and to musicians, how he was a real listener and truly felt music. And I do love that about him. But what truly humbles me and fills me with awe is his pure decency, his humanity, his non-judgment, and his indiscriminate love. I will never be as ‘good’ as President Carter, but it gives me tremendous comfort to know I lived in the era of his goodness.”

From time to time since the film premiered in 2021, I have been fortunate to receive comments like, “You helped change his legacy.” I don’t know about that. There are many misconceptions about Carter. It is not for me or Mary to clear those up. That work is better left to accomplished presidential historians such as Doris Kearns Goodwin and Douglas Brinkley. But hopefully our film reinforces the undeniable truth that Carter was an incredible human being—and establishes a lesser-known truth, that Jimmy Carter was very cool.