As soon as I quit my job — a decision I made unexpectedly when my son was 8 weeks old — I began to encounter headlines that attempted to quantify my new role. “If SAHMs were paid, their salary would be $184K/year,” went a typical one. My son will be 4 on his next birthday, and in my travels across the Internet, I still come across that number at least monthly. It’s a sum that far exceeds any salary I made, but it seemed especially irrelevant once I was doing what felt like both the most relentless and high stakes work of my life. What was the point in knowing my worth in theory, when it was accompanied by nothing material?

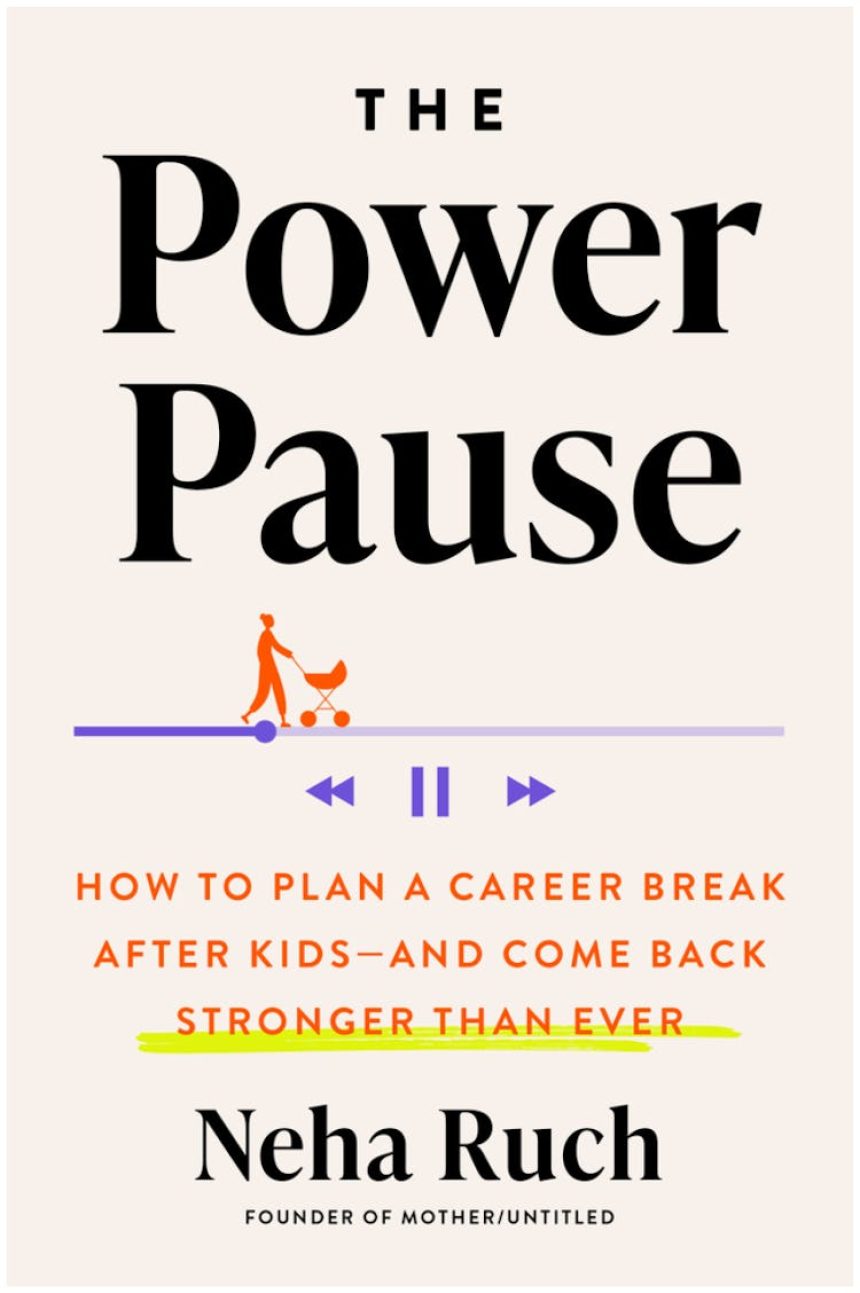

That fantasy six-figures appears, too, early on in The Power Pause: How to Plan a Career Break After Kids — And Come Back Stronger Than Ever by Neha Ruch, founder of the website (and popular Instagram account) Mother Untitled. When she invokes the number, it is to point out that, in her words, “Our work inside the home is critically important and valuable, yet few mothers I’ve met feel like a revered six-figure-earner during their career pauses.” Ruch’s mission is to change that. The Stanford MBA and former brand strategist’s current project, launched after leaving her corporate career following the birth of her kids, is to rebrand stay-at-home motherhood.

It is, perhaps, a role that could use some sprucing up. A perusal of any relevant online comment section, as well as plenty of IRL conversations, will tell you that opinion is split on whether the 21st century SAHM is a pitiable or a privileged figure (neither is a positive assessment). Ruch situates herself in the Lean In, girlboss era, but the stay-at-home mother faced disdain and condescension long before Sheryl Sandberg. It doesn’t help that the role as we conceive of it is largely mythological: In the history that Ruch starts the book off with, she shows how the postwar stay-at-home mother of the popular imagination was a historical aberration that became cemented in our minds thanks to the concurrent invention of television. When people picture the kind of mom who stays home, they’re picturing June Cleaver. When her work is done, Ruch hopes we might instead imagine a striving, multi-hyphenate woman whose years at home don’t condemn her to stagnant invisibility but take her somewhere even better — someone a bit like herself.

Ruch is threading a difficult needle at a time when tradwives dominate media attention and real political energy is aimed at reducing the choices women have gained over the last century. To distance herself from such currents, Ruch identifies her project as a feminist one and repeats the phrase “modern and ambitious” like an incantation against all that. She also sidesteps the mommy wars entirely: “Staying home with your kids isn’t a virtue, and neither is working,” she writes, and notes that “research shows that a parent’s career status has no bearing on the happiness levels of their children.” Instead, her focus is on what a career pause — her reimagining of the dreaded “employment gap” — might mean to the person taking it.

It’s a somewhat surprising book: self-help for people in a stage of life in which selfhood may feel secondary, a professional development manual for those out of a profession.

Midway through the book, Ruch recounts a remark by her husband. though it’s something anyone parenting full time has probably heard before, about how he could never do what she does. This is a comment she has come to understand, she writes, “as a ‘polite’ way of saying, ‘I’m just too complex for at-home parenthood. I need the challenge of work to stay fulfilled.’” Her resistance to this extremely common characterization evades its usual forms — unsubstantiated claims about the negative impacts of day care, lists of a million supermom accomplishments, or conservative talking points — and instead rests on a conceit I haven’t seen articulated elsewhere so clearly. It’s the idea that full-time caregiving can offer an immersive period of personal growth and that this alone might be reason enough to embark on it, if you can swing it.

If you can swing it is, of course, the question that conversations about how we arrange our lives after having kids tends to hinge on: the cost of child care or the impossibility of aligning work and school hours, the ability to take a hit to career progress and retirement earnings. This is why being an at-home parent is usually framed as a privilege, though the reality is more complex. According to some research, stay-at-home mothers in the United States today draw from two different pools: women with little education and income and women with a great deal of both, which is to say those with very few options as well as those with many. (It’s also worth noting that rates of SAHMs are relatively consistent across race and ethnicity, but, counter to what one might assume, white women are the least likely to stay home.)

Though Ruch makes efforts to be inclusive — of mothers whose departure from the workforce is not a choice, moms with medically complex children or additional dependent family members, and single mothers — the book, perhaps in congruence with its air of aspiration, mainly depicts mothers with more. A money coach quoted in the chapter on finances advises adding “$24,000 to the rainy-day fund” before quitting your job and the most down-market profession mentioned in the book is teaching. More often, the mothers featured are lawyers, heads of human resources, directors of strategy, or entrepreneurs.

Ruch’s consideration of how to forge and articulate a new identity during your pause that most excited me, offering a counternarrative to the notion — so pervasive once you are primed to look for it — that to depart employment is to surrender selfhood.

And yet, as a person who, though excessively educated, did not possess a $24,000 rainy-day fund, I’m reluctant to dismiss Ruch’s project on these grounds. After all, what isn’t easier to pull off if you’re wealthy? And to get to a place where the decisions about how we organize our lives as parents can be more than just financial ones, we need not just substantial policy change, but alternative ways of thinking about our options. After all, imagining a more robust range of possibilities for mothers, as The Power Pause tries to do, is a necessary step toward realizing them.

Right now, the truth is that, regardless of your socioeconomic class, becoming a stay-at-home mother is to opt for low-status, unpaid work that in the absence of a social safety net makes you vulnerable in ways people are eager to remind you of at every turn. When I somewhat impulsively quit my own job, those vulnerabilities were the what-ifs ringing in my ears: What if my husband was laid off? What if he died suddenly? What if I could never get another job after time away?

As with parenting in general, it was more common to find cautionary tales than clear upsides. Yet when my son was born, the thought of leaving him to go to the office became unbearable on a kind of soul-body level. Unfortunately, neither the soul nor body seemed like the appropriate grounds for such a major decision, not when surrounded by warnings about each year out of the workforce making you less employable. Beyond those stats, I didn’t even have the language to discuss the choice; at that time in my life, I’d spent significantly more time mulling over David Graeber’s theory of “bullsh*t jobs” than I had “the most important one.” So like many people explaining their work and child care decisions — both those who leave the workforce and those who don’t — I defaulted to money and logistics, like the fact that more than half my paycheck would go to child care. The impossibility of discussing the choice in any other terms, I can see now, only added to my sense of being alone in it.

Maybe The Power Pause would have helped. It’s a somewhat surprising book: self-help for people in a stage of life in which selfhood may feel secondary, a professional development manual for those out of a profession. It’s also optimistic, a handbook to a world that is not yet the norm — one in which spending time out of the workforce after having kids might be seen as something positive not just by employers but also by oneself and the culture at large.

Ruch guides the reader through making the decision to take a career pause, finding footing in your new role, and figuring out how to “grow and learn” during your time out of the workforce with an eye toward an eventual return. She draws on a wide network of experts and the experiences of real mothers. There is plenty of space devoted to the practicalities, not just financial ones but also how to seek support and resist the isolation so many SAHMs report. But it is Ruch’s consideration of how to forge and articulate a new identity during your pause that most excited me, offering a counter-narrative to the notion — so pervasive once you are primed to look for it — that to depart employment is to surrender selfhood.

I will never not be stunned that I could contribute to Social Security when I was answering emails that could have been averted by a Google search but not while keeping my children alive and tended to.

Though most of us spending our days with small children do not feel a sense of abundant time and energy, Ruch insists that there is radical potential in this phase: “When you aren’t going to the office every day and you don’t have a specific return-to-work date and you aren’t under a time crunch to get a new job or climb the ladder, you have the freedom to do all the skill building or hobby dabbling you may have been curious about in the past.” She goes on, “Pursuing hobbies, interests, and play is brave in a culture that has long emphasized productivity, pay, and profit.” Ruch declines here and throughout the book to explicitly name these cultural forces as capitalist — I found myself wishing she would push the argument a bit further and situate a power pause as something with more political potential. The stay-at-home mom as radical anticapitalist would be a compelling argument, but this is not that book.

Instead, the book brims with encouraging accounts of women who use their pauses to launch new, shinier, and kid-compatible careers, often making explicit use of skills they’d employed at home or for free in service of their communities, but the one I keep returning to is less conventional. It’s the story of a former tech employee, Christine Merritt, who discovers a passion for songwriting, sparked almost entirely by a poignant interaction she has with her son before bed one evening. Merritt has no musical background but ends up committing herself to learning songwriting, eventually going back to earn a new degree in it. Now this was a transformation! It’s what I’d wish I’d known to dream of when I stepped off the cliff of paid work myself, an alternate vision to weigh against all the dire ones. Does songwriting pay Merritt’s bills? It doesn’t seem to, or not yet. But isn’t it a symptom of the culture we live in that we are moved to ask that question, instead of whether working in tech ever made her heart sing?

As you might expect, The Power Pause includes plenty of LinkedIn speak. In making the case for support, Ruch writes, “Like any executive, you need to strategically assemble the right support team.” On justifying the cost of child care even when you don’t earn: “Child care should come out of the joint family budget because it supports the collaborative family organization.” For me, leaving the workforce had been in part about escaping this type of thinking and its ubiquitous language, a desire for a life less obviously bound by market obligations — and it exposed how thoroughly my identity and relations were bound up in philosophies of transaction, expectations of compensation and “fairness” that my children rightfully rejected from the moment they were born.

Herein lies the curious tension of The Power Pause: Much of Ruch’s credibility rests on her professional pedigree — the corner office she once had, the six-figure salary she gave up, her impressive resume — but she often gives the impression of someone in recovery from climbing the corporate ladder. Up at night, feeding her son during maternity leave, she experiences “a sense of calm and contentment that I’d been seeking since childhood.” She realizes then that “the prospect of exploring this version of myself as a mother and letting this sense of peace and belonging transform me was too enticing to ignore.” After she leaves her career, she finds that “detaching myself from corporate organizations has allowed me to be myself, exactly as I am.” She tells us that her stated goal while home with her kids was to be the calmest and most content version of herself that she could be. The most resonant parts of the book to me are when she talks about her pause in those terms: as a time of profound growth and self-actualization.

I’ve often wondered, even as I’ve insisted that care work is work, and heeded the calls to label what I do unpaid labor, if work is the right metaphor for parenting at all.

But the “power” in the pause is a promise that something external will come of all of this inner work; in Ruch’s case, a new chapter as an entrepreneur running Mother Untitled. Ruch is clear that she sees inherent worth in caregiving — she says she “could write this whole book arguing that stay-at-home parents deserve (and need) a paycheck for their work” — but in the world we live in, if not the one she is trying to create, her message’s momentum relies on the fact that caring for children will be seen as more valuable when it’s viewed as a “leadership training ground.” I get it. And I also don’t really want to think of my role as helming a tiny domestic corporation, serving as my family’s CEO. Why isn’t being the most present and capable parent I can be enough?

I’ve often wondered, even as I’ve insisted that care work is work, and heeded the calls to label what I do unpaid labor, if work is the right metaphor for parenting at all, even for those of us who do it in lieu of paid employment and so may feel especially inclined to legitimize it in those terms. And legitimization is important if we want social support for caregivers: I will never not be stunned that I could contribute to Social Security and appear in employment statistics when I was answering emails that could have been averted by a Google search but not while keeping my children alive and tended to. Still, so much of what has been transcendent for me about parenthood is how little it resembles anything I did before, especially paid employment. In the days with my children, who are neither my employees nor my employers but something far more complex, I marvel at all the change — mainly theirs, a rate of progress I’d always longed for during workdays that could feel stifling in their sameness, but also, not infrequently, my own. That change feels so powerful to me at times that it seems like it should be a currency all of its own. Maybe what I wish, and what I hope Ruch does too, is that someday, somehow it could be.

Lucy Morris is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in The Cut, Slate, BuzzFeed, and more. She previously wrote for Romper about ‘80s parenting books and when diet culture comes for babies.